Gardens…Evolution…Wonder

The bird was standing in a labyrinth in Dingle, Ireland. Not to project onto the bird – but I was feeling small and alone while I was there – just having totaled a rental car and being kind of adrift about how I would get back to the other end of the country. “That’s what happens when you go to the other end of the country – its about as far away from here as you can get.” This was said to me by the guy towing my car away, as if I had gone to the moon….in terms of distance between Dingle and Ballyvaughan. But remember – Ireland is not much bigger than the state of Wisconsin so it didn’t seem all that far away to me.

[Where you are obviously affects how you see the world.

Trying on different lenses – (however you do that) – always useful.]

I know this is going to sound totally far-fetched (and probably is – but…) I have been thinking about evolution in some rather unconventional ways since I visited Grande Galerie de l’Évolution (Gallery of Evolution) in Paris. Bear with me. SOMEHOW – I want to connect this to gardens….mine, those I saw when I was traveling, and those in SL. Evolutionary?

Housed in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris’ 5th arrondissement, the Gallery traces the evolution of species and is part of the National Museum of Natural History, taking visitors back millions of years, helping them to comprehend the history of the natural world, and how the world came to exist. I found myself thinking about it on all sorts of level – always going back to what David Attenborough has written:

“I know of no pleasure deeper than that which comes from contemplating

the natural world and trying to understand it.”

Each one of us has a story of a million events or actions or people that brought us here. Go back far enough, and this exact moment in your life becomes a rare species, some sort of bizarre evolutionary process that brings us to where we are.

I was taught about evolution as a young person. It makes perfect sense – but because I don’t often have cause to think about it – I didn’t realize (or ever consider) that evolutionary theory would “evolve” in and of itself. Of course it would.

[Remember. Where you are obviously affects how you see the world.

Trying on different lenses – (however you do that) – always useful.]

Lots has happened since Darwin studied finches and Mendel with his peas.

In Evolution without accidents, James A Shapiro writes about genome sequencing (the genome is the entire set of DNA instructions found in a cell), and how it has changed the way we understand how things evolve. There are new genetic processes that we now have knowledge about that natural selection (Darwin) and genetics (Mendel) fail to account for. Until recently (and even now, in some cases) scientists studying outside of this box have been ridiculed because of the belief that gradual accumulation of random mutations was the only reasonable explanation for evolution.

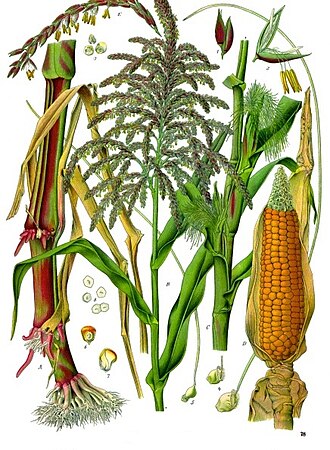

Barbara McClintock, was one of the giants of 20th-century genetics. In the early 1930s, she discovered that X-rays broke chromosomes, and that maize could repair the damage by joining broken ends together. If the rejoined ends came from the same breakage event, the chromosome was restored to its original configuration, but if those ends came from two different breakage events, the chromosomes were restructured.

This discovery revealed an entirely new mechanism of genetic regulation and variability: maize plants were rapidly changing their own genomes through transposable controlling elements (TEs). And moreover, TE changes were nonrandom in two ways. Firstly, the same DNA element could insert repeatedly at new target sites; and, secondly, TE mobility and mutagenic activity was activated by specific organismal stress conditions. The human genome, for example, contains more than 30 times as much TE DNA as it does protein-coding DNA. TEs have played a major role in evolving genome systems for complex properties like immune defenses, embryonic development, and viviparous reproduction in mammals.

This means that cells can cut and splice their own DNA molecules, a capability that Shapiro calls ‘natural genetic engineering’. In certain fish, this kind of ‘alternative splicing’ allows them to fashion protein variants for dealing with different stresses and challenges.

The fact that TEs respond to stress indicates that they are regulated biological entities that play a sensory-guided role in survival and reproduction. The notion of controlled biological processes at the core of organic evolution is plainly incompatible with a purely physicalist explanation, such as random mutations plus natural selection. Biologists now have to incorporate as foundational a recognition that rapid genome reorganisation is not only a feature of all organisms but, evidently, has proved essential for the survival of life on an ecologically diverse and dynamic planet.

Human brain development is created through continuing complex interactions of genetic and environmental influences.

And what does this have to do with gardens?

There are tons of ways to think about gardens. In terms of color, or how they are laid out – or what their purpose is. How structured are they? Or how natural. I have no small amount of wonder for all of the gardens I see throughout the world – whether my own backyard, in Ireland or in Paris….and oddly enough, in SL. How can it be that sometimes pixels / prims can do this? And by THIS I mean inspire wonder.

Is this part of our own evolution – our ability to wander/wonder through all of the beautiful places created in SL – is it a part of how we are evolving? Of course it is not the same as RL. No two experiences are ever the same. But that doesn’t make them less valid, does it? I have these images in my head of all living things (and that would include US) having chromosomes that can change their own genomes either by inserting themselves repeatedly at new target sites; and, secondly, doing it in response to stress conditions. Is a part of that change we make an adaptation to life (and stress) in both a physical and virtual world?

And THAT people – is how an artist can take scientific information, add some wonder – stir it all up in her imagination and propose it as one of the ways / reasons we enjoy our wanderings in virtual gardens and other natural spaces.

[Remember. Where you are obviously affects how you see the world. Trying on different lenses – (however you do that) – always useful.]

Wonder is where it starts, and though wonder is also where it ends, this is no futile path. Whether admiring a patch of moss, a crystal, flower, or golden beetle, a sky full of clouds, a sea with the serene, vast sigh of its swells, or a butterfly wing with its arrangement of crystalline ribs, contours, and the vibrant bezel of its edges, the diverse scripts and ornamentations of its markings, and the infinite, sweet, delightfully inspired transitions and shadings of its colors — whenever I experience part of nature, whether with my eyes or another of the five senses, whenever I feel drawn in, enchanted, opening myself momentarily to its existence and epiphanies, that very moment allows me to forget the avaricious, blind world of human need, and rather than thinking or issuing orders, rather than acquiring or exploiting, fighting or organizing, all I do in that moment is “wonder.” Herman Hesse

This is a series of blog posts about the places, ideas and connections that Lanne Wise muses about while wandering around TNC sites. Lanne is a grateful member of TNC and also keeps a blog, Small Things Worth Seeing, here.